This song is saudade itself.

Its story of love on the rocks was penned by Irving Berlin, with the champagne-fuelled assistance of Dorothy Parker on its last two lines. Addressing their (soon-to-be) estranged lover, its protagonist contemplates a lonely future absent of their company. In this future, the other person is a long way away, in the arms of another. All that is left is a photograph and castles in the air. It is the definition of ‘”a vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist, for something other than the present”‘.

In a fascinating piece for The Atlantic, David Schiff talks of how Irving Berlin’s tunes ‘have a verbal tag and tell a story’, instilling in ‘common American phrases the nervous musical impulse of the modern city’.

Like many other Irving Berlin compositions, this song is deceptive in its simplicity. ‘What’ll I do?’ is its lyrical foundation. The boxy end rhymes of its two verses give a sense of stability – ‘divine’/’mine’, ‘mended’/’ended’, ‘bliss’/’kiss’, ‘descending’/’ending’ – which the choruses proceed to entirely undo. Internal rhymes surge through the choruses like gentle waves, softly eroding what formerly seemed secure. ‘What’ll I do when you are far away / And I am blue, what’ll I do?’ The only lines that lack these repeated internal rhymes are those reflecting on the protagonist’s memento – ‘What’ll I do with just a photograph / To tell my troubles to?’ The ebb and flow of the song’s emotion comes to a temporary moment of stillness with this melancholy image.

It’s been recorded numerous times in vocal and instrumental versions, very often with sentimental strings, as in Frank Sinatra’s 1947 performance. The major key and waltz time sit in a sad tension with the song’s sorrowful lyrics. But desolation and abandonment are not all there is to it. For example, Sarah Vaughan’s 1964 recording, arranged by Benny Carter, is razor-sharp.

What’ll I do? Immediately go on holiday, pound a bunch of drinks, and plot exuberant revenge. Vaughan’s sleek arpeggios are not really about pining. In this devastating live performance on her television show, Judy Garland makes an inspired lyrical adjustment following what seems like a pronunciation misstep: ‘What’ll I do when I am wondering how / You feel just now, what’ll I do?’ Chet Baker’s psychedelic interpretation, recorded in 1974, conjures a parallel universe. It’s beautiful, but I find it deeply antagonising: to me, this protagonist seems to be gaming his interlocutor.

I can’t remember how I first came to know ‘What’ll I Do’, but it’s highly likely that it was via the opening credits of the BBC sitcom Birds of a Feather, in which it is performed by co-stars Pauline Quirke and Linda Robson.

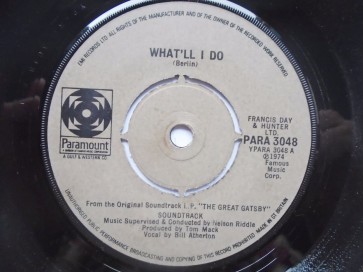

The series had originally used for its own credit sequences Bill Atherton’s recording for the opening credits of The Great Gatsby (1974), directed by Jack Clayton. The choice of ‘What’ll I Do’ for The Great Gatsby is itself a reference to the song’s own genesis: as a member of the Algonquin Round Table, Irving Berlin ran with a set that ‘often partied at the Long Island Gold Coast estate of Herbert Bayard Swope (a figure whom many believed to be the model for Fitzgerald’s Gatsby)’.

Atherton’s tender vocals accompany a gradual close-up on a newspaper clipping – Mia Farrow as Daisy – and a tracking shot of the dissolute, photograph-bedecked luxury of Gatsby’s mansion. The revised Birds of a Feather credits are likewise accompanied by the sweetness of strings, and a selection of photographs. But these are of the series’ two sisters, now cohabiting following the imprisonment of their husbands for armed robbery. And they are photographs of the two actors, taken at various stages of life, that appear to be genuine: Quirke and Robson had grown up together.

For both opening and closing credits of Birds of a Feather, only the first and last choruses are used, stripping the song of romantic association. It is possible to hear reference to the incarcerated husbands. But in juxtaposition to the photographs, it becomes much more prominently about the sisters’ relationship, and the sadness of their former separation through the process of adult life. The cinefilm that graces the closing credits is excruciatingly poignant – from one child’s impossible attempt to feed ice-cream to her bear, to their final wave to the camera, running up the grass into the future. It’s an extraordinary visual gesture to the final lines of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel: ‘So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past’.