This song is the epitome of shifting sands.

Matt Dennis and Thomas Adair wrote ‘Violets For Your Furs’ together in 1941. Appearing on The Rosemary Clooney Show in 1957, Dennis reminisced about the process:

Well this is probably the corniest songwriting story of all time, but my partner and I were sitting in the pub one snowy night back in New York and he was having a beef with the girl he was dating at the time. Sitting there just listening to a combo play the blues, and well, feeling kind of moody anyway, he came up with this song title. It sounded pretty good to me, so I just started working on the melody right there. Believe it or not he wrote the lyrics right on the tablecloth too, and before the evening was over we’d written ourselves this song.

The wintry context of its creation makes its way into Adair’s lyrics. A kind of theatre of memory, the song sketches out a scene between two lovers, nostalgically recalled by the song’s protagonist. As snow drifts down in the Manhattan streets, a man buys a posy of violets for his beloved’s fur coat, which has the enchanting effect of making the chilly situation seem like spring. The song concludes adorably: “You smiled at me so sweetly, since then one thought occurs / That we fell in love completely, the day that I bought you violets for your furs”.

On one level, it’s a simple story of a simpler time: men were chivalrous, women were graceful, furs were the height of sartorial elegance, and love was new. But even on its own terms, setting aside any questions that may or may not arise concerning ‘men’, ‘women’, courtship, and who can procure fresh flowers and furs in Manhattan at the tail end of the Great Depression, the song contains multitudes.

Tommy Dorsey and Frank Sinatra recorded it first in 1941, in an interpretation that conjures divine dinner dances, and the giddy euphoria of falling in love. The moment on the Manhattan street feels like it happened just last week, but also that it’s yet to come. Meanwhile, Sinatra’s sleigh bell-sprinkled 1956 rendition – whose seasonal phrasing is taken by Barry Manilow’s recording – seems to look back to a happy event many Christmasses ago. Johnny Hartman’s extraordinary performance – a tribute to John Coltrane’s – is heavy with deep disappointment. Shirley Horn’s sublime version aches with remembered longing. Beverly Kenney serves up bright and naive entitlement, with a tiny hint of rage: maybe this character didn’t get what they wanted in the end. Stacey Kent delivers a poignant reverie.

Alec Wilder and James T. Maher delight in the way ‘Violets For Your Furs’ “moves and does lovely inventive things”, comparing singer and composer Matt Dennis’s writings to Johnny Mercer’s, which each “suggest the presence of the performer in their composition”. It’s so rich. Its embrace of then and now, whenever these times are in the universe of a given interpretation and whatever has taken place in-between, is magic. Even still, it’s comparatively neglected as a standard, with recordings only in the double digits. No films seem to have taken it up, although it is fleetingly mentioned in a scene in the ninth episode of cancelled ABC drama Six Degrees (2006-2007).

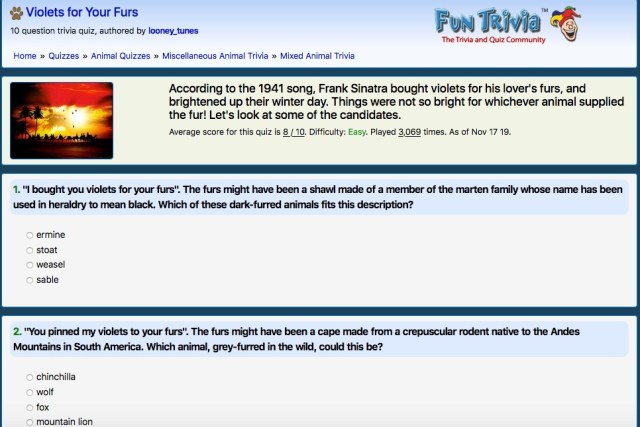

Is that neglect to do with anti-fur politics, as this piano studio proprietor suggests?

(On that issue, this highly specialised quiz about animals = in the running for my most favourite weird internet thing.)

Or is it to do with the somewhat antiquated ritual it describes?

This 2003 sinatrafamily.com thread is started by a forum member who can’t ‘get’ the song, and thinks it’s ‘asinine’. Her contribution prompts a flurry of rebuttals from fellow posters fantasising trips down all kinds of real and imagined memory lanes, some lamenting the decline of civilisation as manifest in casual dress. A lengthy discourse on hats unfolds. Its kind and friendly online banter is a world away from the cultivated vitriol of the contemporary social industry.

These thoughts of animal rights, old school gallantry and polite conversation were front of mind as I wandered around the internet seeking out links to various versions of ‘Violets For Your Furs’. Seeing the cover art for Marty Paich’s I Get A Boot Out Of You (1959) took me aback.

Paich’s magnificently louche arrangement of ‘Violets For Your Furs’ on this album suggests lovers in smoky late night bars. The racy cover art is like a cutesified sexy and highly unsettling anticipation of the shower scene from Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960).

Similarly, Dave Brubeck’s Angel Eyes (1965) features a tremendous hard-swinging version of the song, and a glassy-eyed Terry Reno on its cover. Twenty or so years after ‘Violets For Your Furs’ was composed, second wave feminism was burgeoning, and at the same time beautiful girls stared out from a lot of cover art, in varying states of undress. (I’d call it Playboy-ification, but these album covers are ahead of the Playboy game.) Plus ça change, etc. Romantic love may be protean, and the gentle attentions of ‘Violets For Your Furs’ out of joint with the softcore objectifications of the 1960s. But the patriarchal structures that prop up ‘romance’ are doggedly persistent, for sure.