This song disturbs.

In The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989), as novice vocalist Susie Diamond, Michelle Pfeiffer delivers a captivating performance of a section from ‘More Than You Know’. Former escort Susie has rocked up extremely late for an audition to join the struggling piano duo of Jack (Jeff Bridges) and Frank (Beau Bridges). Following a moment of antagonism with controlling jobsworth Frank, she casts a magic spell over the dilipidated piano showroom with an unexpectedly mesmerising rendition. The selection of lyrics anticipates their unfolding relationships, and the boom and catastrophic bust of the brothers’ business. Frank’s wedding ring gleams in shot as he fights back unexpected emotion.

‘More Than You Know’ first appeared in the short-lived Broadway musical Great Day! addressed by its plantation-owning protagonist to her love interest. For Thomas S. Hischak, the song is ‘a languid yet stately ballad that seems to tumble forth effortlessly as it explains how one’s love is greater than the object of affection can ever realize’. Definitely, but in terms of its overall structure and effect I tend to agree with Alec Wilder and James T. Maher:

The verse is very florid and ‘inspirational’. It isn’t a verse as much as an exclamatory introduction to the chorus. The latter for those who have never heard it, comes as a complete surprise in that it is much less dramatic than the verse.

Wilder and Maher are talking about Vincent Youman’s composition, but the same dynamic applies to Billy Rose and Edward Eliscu’s lyrics.

The sharp distinction between ‘florid’ verse and ‘stately’ chorus accentuates the song’s unfolding of insecurity in love. In the verse, nonchalance (‘Whether you remain or wander / I’m growing fonder of you’) quickly escalates to grandiosity (‘Wouldn’t I be glad to take you? / Give you the break you need’) before the chorus lays out a more consistent scenario: I’ll be around, how you must need me, I know this is just sex for you, please don’t get bored. It’s an extraordinary portrait of self-deception and brutal frankness all at once.

The ups and downs of the song’s story are discomfiting to read on the page – maybe why many versions redact the verse – but so much else is possible in performance.

One of the earliest of the song’s hundreds of recordings, by The Scamps, claws back agency on the part of the protagonist with gentle harmonies and unexpected humour. In a dramatic arrangement, Della Reese openly treads a line between anger and desperate tenderness. Beverly Kenney’s restrained and wistful delivery hints at volcanic passion. Jackie Paris offers unsteady yearning. Dee Dee Bridgewater’s rich performance admits to no vulnerability whatsover.

The song’s uses on-screen are similarly divergent – to take two examples of the five films in which it has featured, Hit the Deck (1955) and The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989). As films, despite massive differences in genre and tone, there are spooky affinities between them: both are about the entertainment business, and social and sexual legitimacy.

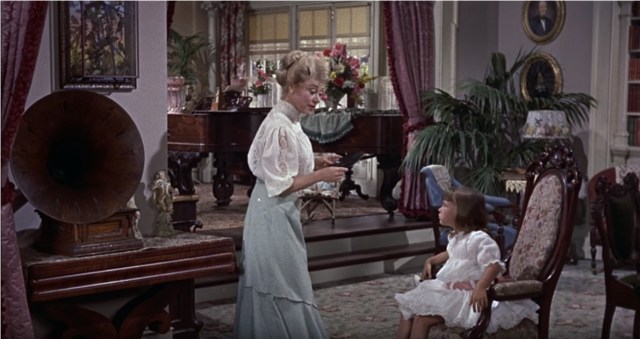

Hit The Deck tells the convoluted story of three couples getting it together. It hinges on a dodgy hotel suite audition undertaken by ingenue Susan (Jane Powell) with the vile actor-manager of a production, also entitled ‘Hit The Deck’, which features musical theatre actress Carol (Debbie Reynolds). Accompanied by fellow naval officers Bill (Tony Martin) and Rico (Vic Damone), all of whom are on shore leave, Danny (Walter Pidgeon) runs to the hotel suite to protect his sister’s chastity. Cue hijinks as the sailors attempt to escape disciplinary action for trashing the suite. Before this pivotal event, Bill sings in ‘Keepin’ Myself For You’ a club cabaret number danced by Ginger (Ann Miller), his fiancee of six years, and Danny horns in on Carol’s dress rehearsal of the suggestive song ‘A Kiss Or Two’.

While all this is going on, Ginger has had enough of waiting around to get married, and unconvincingly dumps Bill for ‘someone else’. ‘More Than You Know’ is his effort to win her back.

It’s a strange choice. The song far better suits Ginger’s own vulnerable position in their long-distance relationship. But then, as a cabaret performer, the film has presented her as from the wrong side of the theatrical and sexual abstinence tracks. Sung by Bill, ‘Whether you’re right / whether you’re wrong’ and ‘Loving may be all you can give’ take on an unpleasant moralising dimension. (Also dodgy: as in The Fabulous Baker Boys’ highly questionable representation of jazz club Henry’s, Ginger’s earlier number ‘The Lady from the Bayou’ racialises desire.) Bill croons, and Ginger distracts herself by tapping on her parakeet’s cage. With the kiss that seals the marital deal, the cage remains prominently in shot – an unusual, pro-Ginger moment of critique in a film that just can’t make up its mind about women and sex.