This song assumes many guises.

‘Gee, Baby, Ain’t I Good To You’ was written in 1929 as a collaboration between bandleader Don Redman and songwriter Andy Razaf. Its lyrics present a person contemplating love and fidelity, and the furs, cars and jewels they give to their significant other as token and guarantee. Recorded first in New York under the name of Redman’s band, McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, in a session featuring a host of Harlem jazz luminaries, Redman performed the lyrics himself.

It’s since been recorded hundreds of times, most recently in a live set by Jeff Goldblum and the Mildred Snitzer Orchestra, with a virtuosic vocal performance by Haley Reinhart which builds from quiet seduction to full-throated euphoria.

In his beautiful biography of Andy Razaf, Barry Singer discusses the ‘pristine craftsmanship’ of the song and its multidimensionality.

‘Ain’t I Good To You?”s lyric question – “Gee baby, ain’t I good to you?” – was in many ways a perfect blues phrase: bittersweet, wry, and plaintive all at once, a question that readily absorbed whatever emotional experience a singer might bring to it – insistence, recalcitrance, determination, despair – the range of possible inflection was endless.

Jose James’ powerful version of the song uneasily suggests control masquerading as love. Redman’s original spoken word performance seems a milder, more hesitant variation on that theme. Meanwhile, Nat King Cole’s 1944 interpretation is kindly and vulnerable: his character sounds like a soft touch being taken for a ride in a situation that will not end well, as the song’s discordant finish hints. In Peggy Lee’s version, her wistful vocal performance is in dialogue with spiky piano improvisation, as if it’s her guy arguing with her, wriggling to get free. Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong’s duet, which tweaks the lyrics, presents a fiery conjugality in which a couple showers one another with gifts. Two additional lines conclude the song: ‘Get me paying taxes of what I gave to you / Gee baby, ain’t I good to you’.

This handful of versions toys with constraints of gender, money and power, exposing the torturous difficulty of human connection. A universe of possibility lives in the song.

At YouTube links to these recordings, references to the problematic Jim Carrey movie The Mask (1994) pop up repeatedly in the comments – ‘SSSSSSSSSSOMEBODY STOP ME! SSSSSSMOKIN”, ‘Just watched The Mask and it brought me here :-)’. Having never seen the film in full before, I didn’t know that mid-way through The Mask is a performance of ‘Gee, Baby, Ain’t I Good To You’ by Cameron Diaz, dubbed by vocalist Susan Boyd.

Carrey stars as Jekyll and Hyde character Stanley Ipkiss, a downtrodden bank clerk living in the Chicago-like Edge City. His accidental acquisition of the magical mask of Loki transforms him into the libidinal Mask by night, unleashing his subdued inner self, which to this point has been given expression only through his fandom of Tex Avery cartoons. (This recent Den of Geek post interprets the film as a parable of alcohol consumption.)

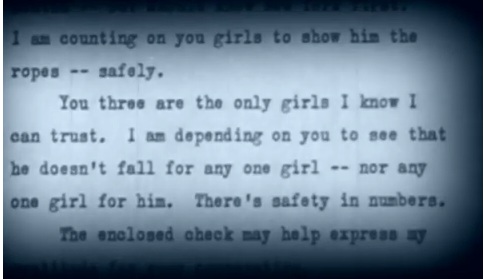

Ipkiss has developed a crush on singer Tina Carlyle (Diaz) thanks to her rain-drenched visit to his bank on a reconnaisance mission for her gangster boyfriend Dorian, who intends to rob the bank as part of a larger city takeover. Hearing that she will give a performance, Ipkiss transforms into the Mask to gain entry to the exclusive Coco Bongo, the club where Carlyle works and Dorian is based, having robbed the bank himself first to pay for his night out.

From the stretch limo that carries the Mask to the club, to Diaz’s appearance onstage and his racy response, the scene draws heavily on the Tex Avery animation ‘Red Hot Riding Hood’ (1943) which appeared earlier in the film, a short which jazzes up Little Red Riding Hood.

Where ‘Red Hot Riding Hood’ satirises the male gaze, The Mask fully signs up to it, and nowhere more explicitly than in this scene. Red Riding Hood’s performance of Bobby Troup’s ‘Daddy’ (1941), a song about getting and being given fancy stuff, begins sweetly and becomes increasingly physically exaggerated, even grotesque. In The Mask, the opposite is the case: here, ‘Gee, Baby, Ain’t I Good To You’ manifests as a story of male satisfaction, and the vehicle for the consistent presentation of Cameron Diaz’s body as alluring temptation. With a lyrical adjustment – ‘I know how to make a good man happy, I treat you right / With lots of love just about every night’ – the overwhelming visuality of the scene veils the delicate ambivalence of Redman and Razaf’s composition about love and gifts.