This song is now, then, and forever.

The recording history of J. Fred Coots and Sam M. Lewis’s ‘For All We Know’, written in 1934, begins merrily with a version by Hal Kemp and His Orchestra, sung by Bob Allen. Its optimistic trills and honeyed vocals belie the song’s depths.

On the surface, ‘For All We Know’ is about a tentative encounter between two people, about to part on an enchanted night. One person speaks to the other of the fleeting quality of the evening and what the future may or may not hold, pledging their heart and soliciting the other person’s love. When Coots first heard Lewis’s lyrics, he thought they were ‘worthy of great poetry’, and promptly promised him $200 of IOUs.

The verse, as performed by Billie Holiday, Aretha Franklin and Bette Midler, locks down the song’s story as one of romantic love (‘A kiss that is never tasted / Forever and ever is wasted’). (Susannah McCorkle and Gladys Knight’s alternative verse intros are variations on that theme.) But Lewis’s words in the choruses are nothing short of a meditation on human existence itself: the experience of love, loss, consciousness, and temporality.

For all we know

We may never meet again

Before you go

Make this moment sweet againWe won’t say ‘goodnight’

Until the last minute

I’ll hold out my hand

And my heart will be in itFor all we know

This may only be a dream

We come and go

Like a ripple on a streamSo love me tonight

Tomorrow was made for some

Tomorrow may never come

For all we know

My favourite versions as of now are by Brad Mehldau, Bill Evans and Jose James and Jef Neve, each one tender and devastating in its own way.

But given the sheer quantity of interpretations, many of them straight ahead – one even by Ken Dodd – it’s weird that the first one I ever heard, again and again, should have been Nina Simone’s radical 1958 reworking. As she put it to Steve Allen in 1964, she interpreted the song in ‘a hymn-Bach-like way’. In her arrangement, whose melody departs substantially from the original, the eighteenth and twentieth centuries touch: a reflection in performance of the lyrics’ attention to endurance and transience.

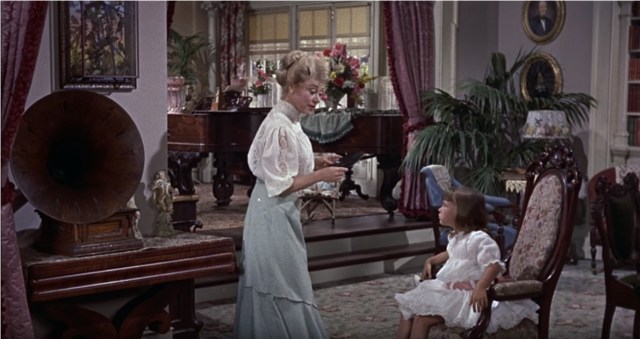

With Joan Plowright as an elderly widow and Rupert Friend as her surrogate grandson Ludo, Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont (2005) does much more with the song than simply include Rosemary Clooney’s version in the end credits. Endurance and transience pervade the film: Mrs Palfrey’s recent loss, her arrival in London to stay long-term at a mediocre hotel, her daughter and actual grandson’s neglect, and her accidental encounter with Ludo, which becomes a tender friendship.

The film is uneven and sometimes quite strange, but this scene is lovely. At Ludo’s flat, Mrs Palfrey has reminisced about falling in love with her husband, including a twinkling nod to their healthy sex life, and days out in Beaulieu. Ludo asks her another question, and an unexpected, touching serenade unfolds.

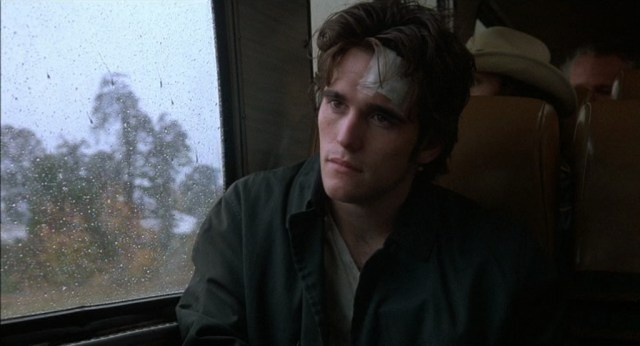

In Gus Van Sant’s Drugstore Cowboy (1989), set in 1971, Abbey Lincoln’s gut-wrenching interpretation is used repeatedly to speak of the dangerous tenacity of addiction – from the opening sequence, which introduces junkie Bob (Matt Dillon), sweating from a seeming overdose on an ambulance stretcher, to his earlier bus ride back to Portland to enter a methadone programme, to the film’s final moments, which return us to the ambulance.

The first ambulance scene, accompanied by the song, has an ironic, hallucinatory quality, compounded with a cut to a cinefilm of Bob with his crew of fellow addicts and thieves.

Later, Bob gazes silently through the misted, rain-spattered window of the bus at the agricultural landscape around.

Adrenalised pharmacy and hospital heists, obsessive superstitions, and violence have given way to a more prosaic reality, which the film complicates with the lyric ‘For all we know / This may only be a dream’. ‘We come and we go / Like the ripples in a stream’ plays over shots of street drinkers gathered outside decrepit storefronts. ‘So love me tonight / Tomorrow was made for some / Tomorrow may never come / For all we know’ suggests both hope and desperation as Bob enters his new abode, the St Francis Hotel.

The last moments in the ambulance, as he struggles not with an overdose but a revenge gunshot injury from a dealer, make clear that Bob intends to abandon clock-time and production line work, and return to his life as a junkie. As Abbey Lincoln sings the song’s final choruses, contemplating the ebbs and flows of time and love, Bob explains.

It’s this fucking life. You never know what’s going to happen next. […] See, most people, they don’t know how they’re going to feel from one minute to the next. But a dope fiend has a pretty good idea. All you gotta do is look at the labels on the little bottles.

On his way to ‘the fattest pharmacy in town’, he wants to live. It’s an incredible use of the subtleties of this wonderful song, which can accommodate the paradox of hedonistic control as well as gentle acceptance of the future’s sadnesses and joys, which so quickly become the past.