This song isn’t having it.

Ann Ronell – a female trailblazer in the sphere of Hollywood musical direction and Broadway composition – originated this wonderful chronicle of heartbreak in 1932. A publishing colleague of Irving Berlin rejected it for being too technically complicated, but support from Berlin himself brought the song to radio broadcast and wider critical and commercial success.

Willow weep for me

Willow weep for me

Bend your branches green along the stream that runs to sea

Listen to my plea

Hear me willow and weep for me

Gone my lovers’ dream

Lovely summer dream

Gone and left me here to weep my tears into the stream

Sad as I can be

Hear me willow and weep for me

Whisper to the wind and say that love has sinned

Left my heart a-breaking, and making a moan

Murmur to the night to hide its starry light

So none will see me sighing and crying all alone

Weeping willow tree

Weep in sympathy

Bend your branches down along the ground and cover me

When the shadows fall, hear me willow and weep for me

While hearing out their lonely protagonist’s pain, these lyrics wink theatrically: love in its entirety has “sinned” because the “lovely summer dream” of a seasonal romance hasn’t worked out for you? All the stars in the night sky should be obliterated to conceal your unique misery? Come on. There’s no shame in sadness.

Ronell’s celebrated, much recorded composition warmly presses that argument forward – in particular the major key in the A sections, its sing-song octave leap (Ted Gioia: “a vertiginous plunge followed by a reassuring triplet bounce unlike anything else in the jazz repertoire of the era”), and the way in which, as Alec Wilder notes, “the accompaniment moves into double time and out again the next measure”. Edward Jablonski interprets this choice as signifying “agitated stress”, but I’m not sure that’s it. Consider, for example, Ella Fitzgerald’s 1959 recording. “Listen to my plea”, entreats the song’s protagonist. Amid the dreaminess of Frank DeVol’s orchestral arrangement, this rhythmic shift counterargues: no, you need to shake things up.

The song’s appearance in the Marx Brothers’ Love Happy (1949) – a crime caper which brings together a diamond heist and a Broadway revue – sets off its refusal of the role of romantic victim in an utterly surprising way.

Ann Ronell scored Love Happy, and oversaw Frank Perkins’ instrumental arrangement of ‘Willow Weep for Me’ for one of the Broadway revue’s numbers. Choregraphed by Billy Daniel, it presents an extraordinary burlesque staging of the figure of Miss Sadie Thompson.

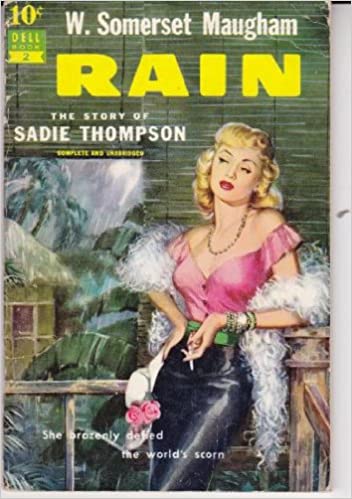

Sadie Thompson is a character in ‘Rain’ (1921), a short story by W. Somerset Maugham set in American Samoa. A ship’s crew member contracts measles, and its passengers are required to remain in port at Pago Pago for a period of quarantine: Dr and Mrs Macphail, missionary couple the Davidsons (ordinarily stationed elsewhere), and Sadie Thompson herself. All are offered accommodation in rooms above a shop. Sadie Thompson entertains sailors in her quarters, playing her gramophone loudly, to the the Davidsons’ infinite disapproval. They quickly infer that, having boarded at Iwelei (“plague spot of Honolulu. The Red Light district”), she is a prostitute, and Davidson himself undertakes to convert her. The missionary programme is vicious: the Davidsons expunge local practices of dancing and dress, impose fines on those who refuse to comply, and delight in destroying associates whose morality they deem insufficient. Davidson’s patriarchal fanaticism – of Sadie, he declares: “‘I want to put in her heart the passionate desire to be punished so that at the end, even if I offered to let her go, she would refuse'” – culminates in what the story very strongly implies is his rape of Sadie and his grisly death by cutting his own throat.

For Victoria Kuttainen, ‘Rain’ dramatises how missionary, medical and cultural regimes collide in the the “colonial, modernising Pacific”. She proposes that Somerset Maugham – both a literary figure and prolific writer for stage and screen – was acutely aware of the imagistic power of “fantasies of seductive starlets and beguiling tropical scenes”, and that his narrative choices comment on the performative power of speculation: other characters are given to report on Sadie’s conduct. In the diverse theatrical and cinematic adaptations of ‘Rain’,* meanwhile, “spectacle replaces speculation”. Stagings of Sadie melodramatically exoticise and evacuate the story of critical force.

The number in Love Happy quotes and exaggerates elements of these adaptations. It sweeps almost every hint of violence away, and reimagines the scenario as a comedy.

In this cartoon tropics, Sadie’s beau, Sergeant O’Hara (played by ‘Paul Valentine’, played by Mike Johnson) – a character introduced in these adaptations – places the needle on the gramophone, and the siren rasp of ‘Willow Weep For Me’ summons Sadie (played by ‘Maggie Phillips’, played by Vera-Ellen) to the stage. Marines gawp as she struts in, her hand magically conjuring her own spotlight. She roams about the stage with comic suggestiveness, occasionally knocking these uniformed men down like dominoes, while O’Hara gazes at her with deep desire. When, as in the story, Davidson (House Peters Jr.) stops the gramophone’s music, a drumbeat commences and a group representing Samoan dancers wearing what resemble lavalava enter the stage, supporting Sadie to continue – a section which trades in racialised stereotyping, places Sadie at its centre, but suggests collective solidarity between she and the islanders against the forces of missionary control. Davidson has failed, and exuberant music and dancing prevail. The gramophone resumes, and a whistle sends the Marines back, who have rushed Sadie like a pack of dogs. The number concludes softly: Sadie and O’Hara stand intimately together before the auditorium of the Broadway theatre to scattered applause.**

This larger-than-life musical rendition both sends up and luxuriates in the cultural habit of looking at Sadie. The lyrics and their sadness ghost the scene, a reminder of the tragedy of ‘Rain’, but here underscoring how Sadie just gets to go about her business.

Before watching the film, I had heard ‘Willow Weep for Me’ only in versions accentuating its bluesiness, as in the powerful recordings by Billie Holiday, Dinah Washington and Etta James, and Sarah Vaughan’s magical and hilarious live performance. With the exception of Stan Kenton’s 1946 arrangement featuring June Christy, the handful of recordings that precede Love Happy are a lively mix of foxtrot and cabaret, and a far cry from the sorrowful sentimentality of other later versions: Frank Sinatra, Julie London, Tony Bennett.

It begs so many questions: about the mood Ann Ronell originally intended for the song, how this scene in Love Happy was conceived and by whom,*** the direction of subsequent recordings. Regardless, it strikes me that its author’s well-documented determination, ambition, kindness and vivacity are of a piece with ‘Willow Weep for Me’. It is a song that “does exactly what it pleases”, recognising social and emotional limits, but isn’t about to accept them.

*John Colton & Clemence Randolph’s play Rain: a Play in Three Acts (1923); Sadie Thompson (1928), starring Gloria Swanson; Rain (1932), starring Joan Crawford; and Miss Sadie Thompson (1953), starring Rita Hayworth.

**Paul’s subsequent instruction to Maggie – “now go change into your ballet costume” – is arguably a misogynistic gag playing on the historical intersection of ballet and sex work.

***An edition of Film Music Notes speaks favourably of “the producer who allowed the composer select co-workers of her own choice wherever possible, thus assuring maximum of compatible tastes and efforts to musical production with minimum personnel”.