This song is not what it seems.

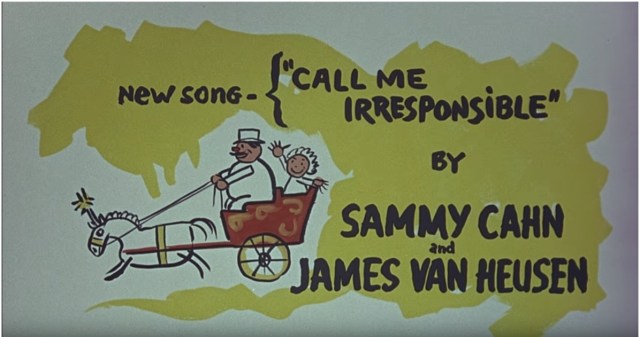

Scores of versions of ‘Call Me Irresponsible’ have been released since Jimmy Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn wrote it in 1962. It was prepared for film comedy Papa’s Delicate Condition (1963), in which it appears first as a wordless lullaby played by a child’s wind-up toy. In 1963 alone, at least seven artists recorded it, among them Frank Sinatra, Julie London and Dinah Washington – the exuberant cadenzas that Washington performs at the end of her version since featuring on numerous adverts and television trailers. (The YouTube link below lists its source as Totally Commercials: the Essential Commercials Album, released in 1998.) I’m so familiar with her performance’s passionate take that reflecting on the song recently, I realised I’d never really understood its lyrics.

My superficial impression: reckless, spontaneous love!

It turns out the song is not about that.

Two short, magnificently crafted choruses give us an inconsistent character shamelessly cajoling their loved one. The character justifies their sketchy behaviour by virtue of their romantic sensibilities (“Rainbows, I’m inclined to pursue”) and their strength of feeling for the other person. In the extraordinary lines “Do my foolish alibis bore you? / Well, I’m not too clever, I just adore you”, a mere fifteen words deftly establish a relationship history and execute a smooth rhetorical confidence trick.

Set apart from the film, this Academy Award-winning song’s interpretative possibilities arguably range from ‘adorable if unrepentant’ to ‘sociopathic’. Compare and contrast Tony Bennett’s puppyish plaintiveness and Julie London’s Shere Khan.

On this basis, ‘Call Me Irresponsible’ is tough to accept in terms of love – unless being backed into an emotional corner is your thing. In its cinematic context, the song’s story takes on another aspect.

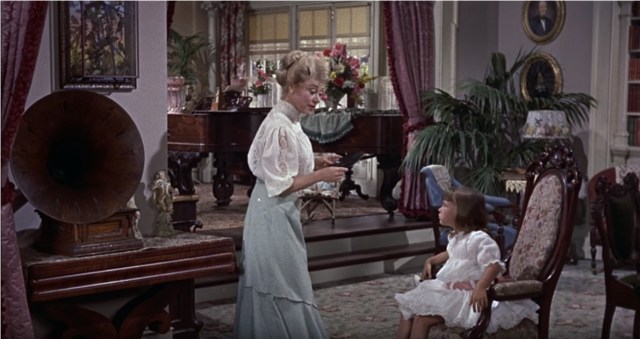

Papa’s Delicate Condition centres around the Griffith family and their salubrious small-town life in Texas. Jack Griffith (Jackie Gleason) is a railway superintendent whose excessive generosity and alcohol dependency together engender recurring marital crises. His church-going, recital-hosting wife Amberlyn (Glynis Johns) is status-conscious and controlling, though not without spark. Their teenage daughter Augusta (Laurel Goodwin) is likewise. Meanwhile, Jack is flamboyant and gregarious, qualities which delight their six year old daughter Corinne (Linda Bruhl) – in real life, a silent film actress and author of the memoir on which the film is based.

In the opening scene, Amberlyn distastefully removes from the gramophone a recording of ‘Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home‘ (1902) as Corinne protests. The film is critical of Amberlyn – jawdroppingly, in these introductory moments she calls the child “my little consolation prize” directly to her face – but though Jack is its hero, it is not uncritical of him: we first meet him on a steam train, enthusiastically belting out ‘Bill Bailey’ and enjoying the lion’s share of a bottle of bourbon in the company of a driver and stoker.

With modified lyrics, a harmonious family rendition of ‘Bill Bailey’ also wraps the whole drama up, raising a great many questions on the film’s uses of that song and their racial and historical politics.

Jack’s ‘delicate condition’ is his regular drunkenness, which leads him to engage in various rash schemes: tricking a man into repainting his ugly house to please Amberlyn, buying a drugstore to rescue a downtrodden assistant from its owner, and finally being hoodwinked himself into purchasing a failing circus so he can give its show-pony to Corinne. This is the last straw for Amberlyn, who gathers up her daughters and flees to her father’s house.

‘Call Me Irresponsible’ marks this moment of abandonment.

This scene – the first and only in this family-friendly comedy in which we see Jack unmistakably drunk – is incredibly sad.

The instrumentation is gentle, but Gleason’s performance of the song is unshrinking. The scene’s visual comparison of the automated and lifeless dolls in Corinne’s room with the bereft husband, his reproachful gaze at himself in the mirror, and his one-sided conversation with his surrogate wife-dummy all speak of patterns of (self) destruction. (The pat to the dummy’s hip is objectionable enough, but in a stunningly aggressive moment directly after this clip, he drops his empty glass into the dummy through its neck.)

By the end of the film, husband and wife will have reconciled. He will be sober; she will have ceded control. But this poignant scene shows the song’s narrative to be based not in the plenitude of love, but a man’s struggle with himself.