This song is unexpected.

Karl Suessdorf and John Blackburn’s 1944 classic ‘Moonlight in Vermont’ features on Stardust (1978), Willie Nelson’s first album of jazz standards. His spacious interpretation became the surprise favourite of its lyricist. Blackburn’s nephew Bill Rudman reflects on his uncle’s reaction for jazz podcast I’ve Heard That Song Before:

He just couldn’t hear in his head how ‘Moonlight in Vermont’ could sort of cross over and be done by ostensibly a country singer. So he just didn’t believe that it was going to be any good at all, and when the LP came out he was just blown away by it.

Willie Nelson’s arrangement is tender and expansive: a solitary moonlit wish in the autumn is realised as a shared enchantment in the summer. Hope and desire are there, but they are unhurried. Things grow at their own pace.

For musicologist K. J. McElrath, Suessdorf’s beautiful composition’s “harmonic progression – quite advanced for its time and heralding the advent of ‘cool’ – makes sophisticated use of simple elements”. The same sophisticated simplicity applies to Blackburn’s lyrics.

Pennies in a stream

Falling leaves, a sycamore

Moonlight in Vermont

Icy finger waves

Ski trails on a mountain side

Snowlight in Vermont

Telegraph cables, they sing down the highway

And travel each bend in the road

People who meet in this romantic setting

Are so hypnotized by the lovely

Evening summer breeze

Warbling of a meadowlark

Moonlight in Vermont

You and I and moonlight in Vermont

The song conspicuously lacks a rhyme scheme. Less obvious is the haiku structure of its A sections. Each phrase obliquely describes an event, trusting its audience to make their own sense of what’s happening without the need for exposition. “Pennies in a stream”: have these coins been thrown there recently, or are they the rusted evidence of past wishful visits, or do they perhaps signify the people (who are not necessarily lovers) at the heart of the song’s story, or represent an idea of the flux of human existence? These four words in combination harbour all these possibilities and more. And the sensate evocations of “icy finger waves”, electric telegraph cables that “sing”, luminescence of “snowlight” – together, these images refuse pastoral nostalgia, instead tracing out modern holidaymaking amid the larger magic of seasonal change. The transition from the B section to the final A uncannily skips over spring, spiriting us directly from winter to summer – a time when, having nested, meadowlarks begin to sing again. It is brilliant.

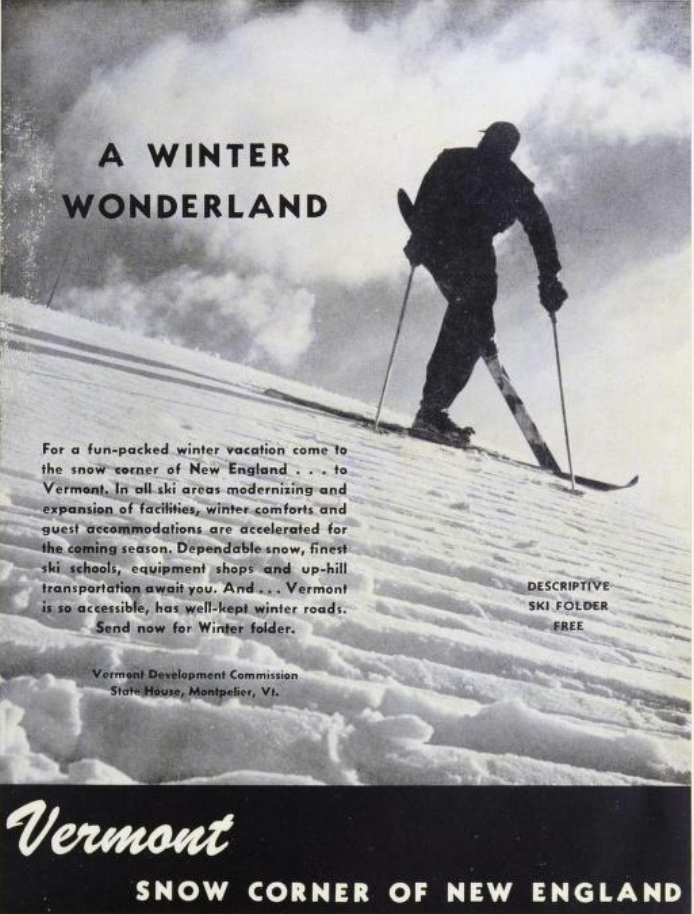

It seems bizarre that people would want to mess with this poetry, but mess with it they have. The most radical example is Jo Stafford’s recording for an album entitled Ski Trails (1956), whose comprehensive rewrite makes winter of the whole thing. In Andy Williams’ live concert performance, the lines “snowflakes in the wind, blanketing the countryside” likewise obliterate the balmy summer of the original.

These specific lyrical choices, and the song’s rocketing popularity in the 1950s, could arguably be to do with skiing. As historian Andrew Denning has it, skiing was “the quintessence of that defining strain of postwar consumer culture: democratized luxury”. This was certainly the case in Vermont, where magazine Vermont Life aggressively promoted “the slopes of Vermont as a nearly year-round vacation destination” throughout the 1950s. To be ultra-specific, it presented Vermont as “a series of vacation areas catering to the modern family man from out of town looking for an all-encompassing winter escape”. What better snowy venue for a departure from routine, for the experience of the once-in-a-lifetime, unrepeatable romance fantasised by these recordings.

The many vocal interpretations of the song run the full stylistic gamut. Particularly enjoyable is its first outing, Billy Butterfield’s big band arrangement with Margaret Whiting – also Betty Carter’s early performance with the Ray Bryant Trio, the excessive vocal harmonies of the Lewis Sisters, Billy Stewart’s soulful re-imagining, Ella Fitzgerald’s intimate dialogue with Joe Pass. But I will say that it is possible to have too much of a good thing. Listening to tens of performances of once-in-a-lifetime, unrepeatable romance fantasies on the bounce is akin to eating a lot of cake: beyond a certain point the experience is empty and just a bit much.

Among the handful of films that include the song is the recent Hallmark TV movie Moonlight in Vermont (2017): “After Fiona [Lacey Chabert] gets dumped, she escapes to her family’s Vermont Inn for a few days to evaluate her life. When her ex Nate [Jesse Moss] shows up with a new girlfriend, Fiona devises a plan to win him back: pretend head chef Derek [Carlo Marks] is her new boyfriend.”

A Kindle search for the movie’s novelisation unexpectedly revealed other, self-published novels of the same name. These include a 2013 country house murder mystery on the model of Agatha Christie (page turner, holds out promise of subverting patriarchal constructs, just doesn’t) and the eleventh instalment in Olivia Gaines’ Modern Mail Order Brides series of romance novels, released in 2020 (the same, to an outlandish comedic degree).

But back to the movie. Moonlight in Vermont, a classic opposites attract scenario, is totally enjoyable, escapist, and implausible. Its characters say and do the most illogical things. Savvy and practical Manhattan real estate agent Fiona wears four inch spike heeled boots to walk in the snowy fields with Derek so she can look hot in front of her ex. Chef Derek, a man whose profession is predicated on the capacity to follow instructions, insists on savouring pancakes slowly in the context of a ‘how many pancakes can you eat in 60 seconds’ contest at the town’s annual Maple Faire. The town’s mayor presides over this contest, and later adjudicates a maple syrup tasting contest in a completely different shop, as if contests are his only job. The ex Nate, crazed with competitive jealousy, snippily declares to his new girlfriend “I’m counting on you here” to beat Fiona and Derek in the maple syrup tasting contest. Thus the movie sets up the beginnings of romance between Fiona and Derek: an enjoyable dinner at the inn, in which each listens with genuine interest to what the other is saying. In the light of the movie’s other strange situations, this conversation seems like the height of real intimacy. It was weird and I loved all of it.

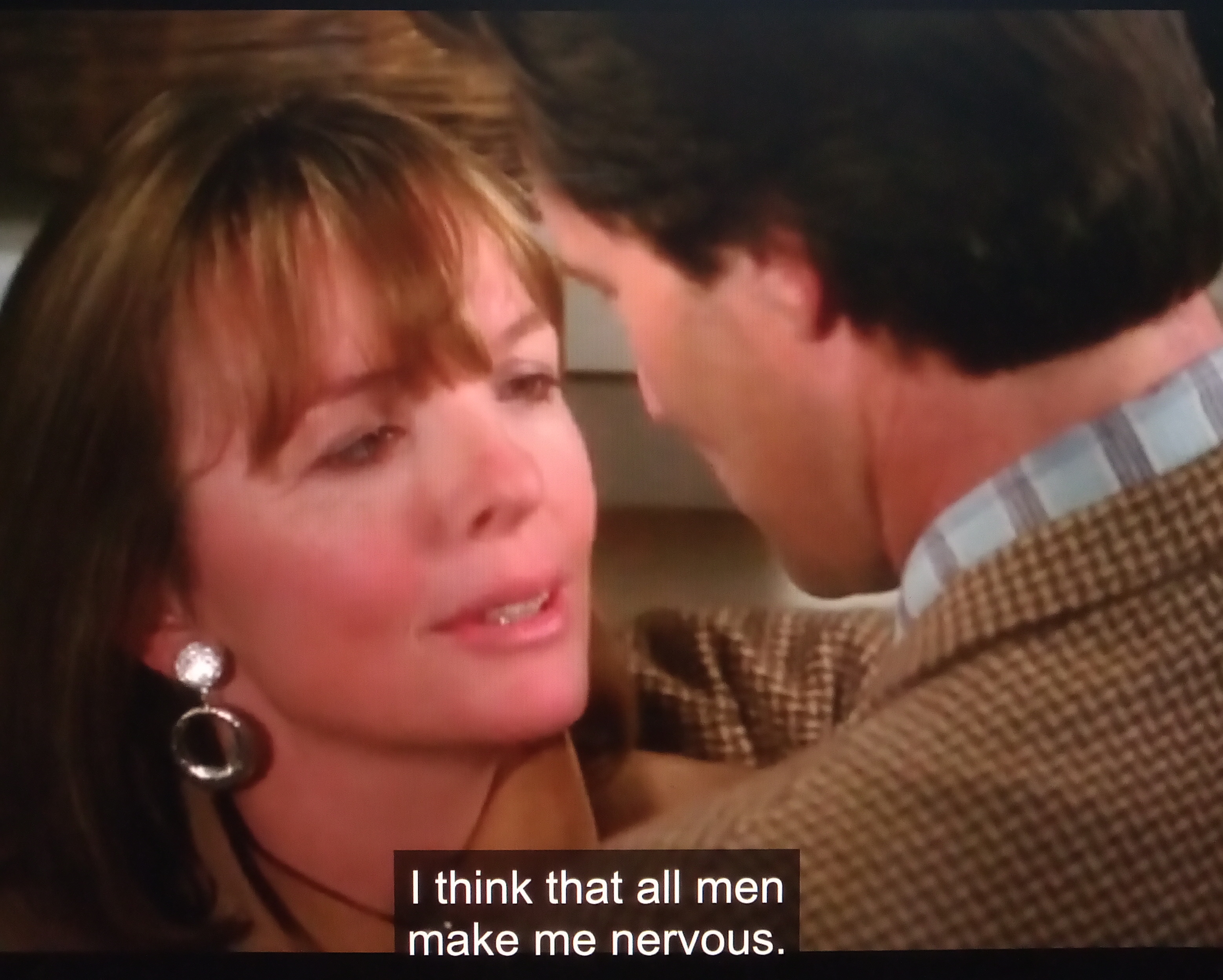

What I take from Moonlight in Vermont is this: some of the appeal of this kind of romantic plotline may be to do with the promise of respite from what Jane Ward calls the tragedy of heterosexuality. Part of that tragedy consists in attachment to “the heteroerotic fantasy of binary, biologically determined, and naturally hierarchical gender oppositeness” (cf. all of the above, plus the leads’ opening barbs: “Vermont lumberjack” / “New York princess”). In moments of beautiful utopian connection, this powerful and damaging nonsense falls away. Supplementary evidence: Baby Boom (1987), ‘Moonlight in Vermont’-having comedy of the nightmare struggle of career woman J.C. (Diane Keaton) against a patriarchal culture hostile to motherhood. Here, having found a new life in Vermont, she is getting together with vet Jeff (Sam Shepard).

Of course heteroerotic fantasies are inevitably re-established: for a female romantic protagonist, it’s true love or bust, and four days in to her visit, Fiona decides to quit New York and move to Vermont. The openness of ‘Moonlight in Vermont’ as a song makes it highly amenable to whirlwind stories of romantic destiny, but also to performances like Willie Nelson’s, a story of ease and grace that makes no demands, is in no rush at all.