This song is all about show.

Until it isn’t, that is. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

‘I’m Thru With Love’ is a work of necessary contradiction. A deep ocean of a song, twinkling with glorious sunlight, it brings grief and optimism into sweet contact. Its lyrics, by the prolific Gus Kahn, see a depressed, abandoned character talking to their ex-lover, uncompromisingly declaring time not only on all future relationships, but on love itself. But amid Matty Malneck and Fud Livingston’s bright composition, this story shifts its shape. It’s so much more than a “melancholy torch song that also has a touch of hope in it“, though it is also exactly that.

With the exception of the 1931 recordings by Lee Morse and Bing Crosby, and some later versions like Tony Bennett’s and Joe Williams’s, few vocalists address themselves to the verse:

I have given you my true love,

But you love

A new love.

What am I supposed to do now,

With you now,

You’re through now?

You’ll be on your merry way,

And there’s only this to say:

In this subtle passage, “love” is something bestowed, an action, and an object of desire, and “now” both a moment in time and a state of being. “You” becomes a psychological problem to be solved somehow. The nuance of these simple repetitions shows their author, as Gottlieb and Kimball write of Gus Kahn, to be “a superb and meticulous craftsman who made a lyric seem easy, even inevitable, rather than calling attention to its ingenuity or wit“. And although the choruses can stand alone magnificently, the verse frames “I’m through with love” as an embittered retort.

At least as it reads on paper, this retort comes from someone whose limited horizons, through this relationship, were briefly extended beyond their own front door. Now it’s over, they have “Said ‘Adieu’ to love / ‘Don’t ever call again'”. The staginess of these quotation marks, as printed in Gottlieb and Kimball’s book, suggests a certain kind of uptight formality – as does the terrible tragedy of the second chorus:

I’ve locked my heart,

I’ll keep my feelings there,

I have stocked my heart

With icy frigidaire.

And I mean to care for no-one,

Because I’m through with love.

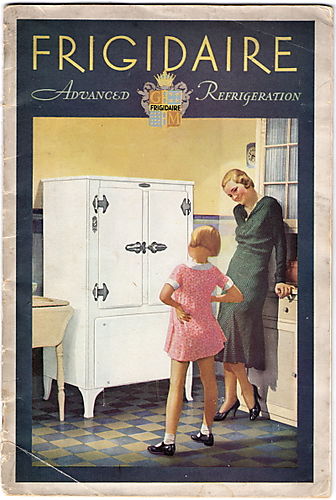

Frigidaire! Not only is the warm human body correlated with an (empty) household appliance, but the refrigerator as such is the reference of choice for this person! Fridge facts: Frigidaire launched the first electric “self-contained refrigerator” onto the market in 1923, the brand quickly becoming synonymous with the thing itself.

On the left is an ad for a 1927 model costing $180 – a value of $2,613.29 in 2020. And on the right, the front cover of a Frigidaire catalogue from 1931, the year of ‘I’m Thru With Love”s release. This image introduces a fascinating blogpost on Frigidaire by Liza Cowan, who gives this shrewd take on its idealisation of domesticity: “nothing says loving like a full fridge“.

All this is to say that the song’s images propose the protagonist as someone who naively thought that they were bopping their way to marriage, or a lonely wife whose affair with someone popular and sociable (“You didn’t need me for you had your share / Of slaves around you to hound you and swear, / With deep emotion, devotion to you”) lifted her beyond marital disappointments.

It’s all very melodramatic, and the song knows it. The major melody in the A sections soothes the narrative’s histrionics, while gut-wrenching chord choices and a sorrowful blue note gently affirm suffering. The B section makes a dramatic leap up to a minor key to emphasise its opening rhetorical question (“Why did you lead me to think you could care”), but doesn’t linger there long. Music puts the words at a distance from themselves, opening out all kinds of alternatives to unadulterated misery.

There are some devastating interpretations – see Etta Jones, Diana Krall, Mark Murphy, Arthur Prysock – but even these performances can’t help but slide into a kind of reflexive self-staging. Some versions are absolutely gigantic (Sallie Blair, Joan Merrill). Others exude an affecting warmth, even contentment (Carmen McRae, Ella Fitzgerald). Still others are in ‘wash that man right out of my hair’ high spirits (Sarah Vaughan, Jane Monheit). It’s a range of moods well sketched out in Swedish pianist Matti Ollikainenin’s ironic solo performance. Listening through multiple recordings on the trot makes for an experience not of utter desolation, as might be expected, but fun born of sadness that doesn’t take itself too seriously.

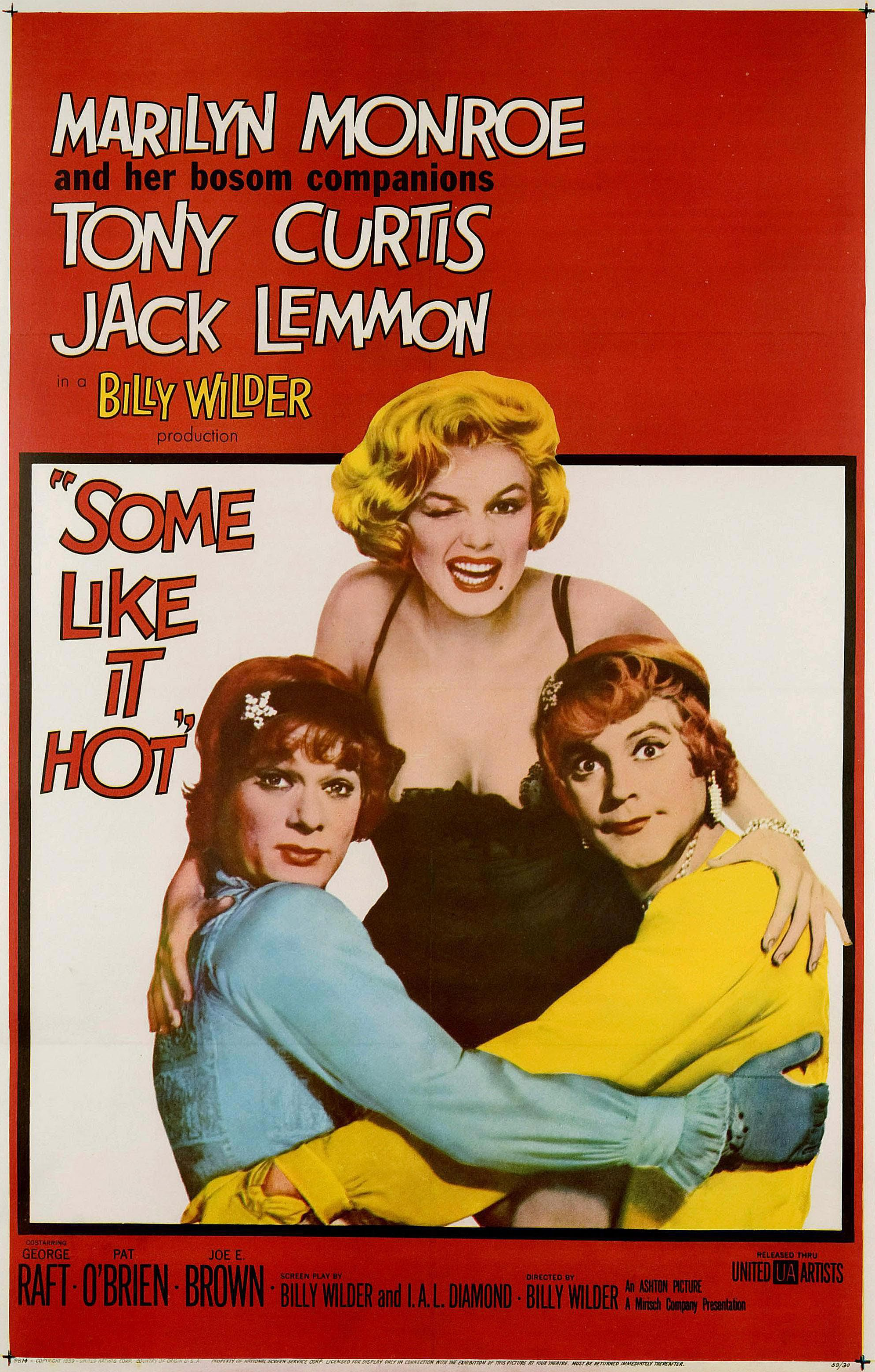

It seems apt then that the song’s most famous outing on screen should be in Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot (1959), a film comedy hingeing on disguise and an homage to multiple cinematic genres. As New York Times critic Manohla Dargis puts it, the film “feels like it was directed inside gigantic quotation marks“.

On-the-run jazz musicians Joe (Tony Curtis) and Jerry (Jack Lemmon) pass themselves off as ‘Josephine’ and ‘Daphne’ to join an all-female touring band. (Sidenote: the film’s musical supervisor was Matty Malneck, and its unreal lineup of musicians included Barney Kessel, Art Pepper and John Williams (yes).) To entice its chanteuse Sugar Kane (Marilyn Monroe), who intends to overcome her “thing for saxophonists” by snagging a Miami millionaire, saxophonist Joe masquerades as magnate Shell Oil Junior, and contrives to have her seduce him aboard a yacht appropriated from actual millionaire Osgood Fielding III (Joe E. Brown), himself in hot pursuit of Daphne.

In the wake of Junior’s sudden departure, heartbroken Sugar sings ‘I’m Thru With Love’, her unhappiness unnoticed by everyone but Josephine, hidden behind a drape, realisation gradually dawning.

Marilyn Monroe’s tremulous performance musters stock gestures of feminine anguish, melting them into other, more authentic-seeming moments of emotion. The depth of her sadness and the euphoria and poignancy of the kiss she and Jo(e)sephine then share are totally conditional upon the layers of comedic artifice the film painstakingly constructs.

“None of that, Sugar. No guy is worth it!” ‘I’m Thru With Nonsense That Is An Obstacle To My Own Flourishing’,* we might then say, as love is discovered to be its own reward.

*Adaptation after Lauren Berlant.